There’s a theory – in Whitewater and other places – that good policy comes from having as many ‘adults in the room’ (that is, as many established & mature people) as possible. I’d say that’s necessary, but insufficient. Relying only on the established & mature, without specific consideration of discernment and insight, relies on too little.

One has to ask: what do you believe, and why do you believe it?

Asking what one believes, and why one believes it, should be an ongoing exercise. Circumstances change; one evaluates anew by what exists now, not on what was, or on what one thinks about oneself.

In the last Whitewater Schools referendum, I assumed (incorrectly) that the vote would be close, and that even the place of the referendum question on the ballot might prove significant.

Looking back, those assumptions were wrong: the referendum carried well enough, and ballot position probably made little if any difference.

I thought as I did because previous referenda in Whitewater had been contentious. That was, however, some time ago.

Looking at referenda results now, from across the state, it’s clear that an overwhelming number of referenda pass (74 of 76 referenda from the February 2016 elections passed).

What does this mean? A few new assumptions and questions:

1. A majority of voters will support more spending for schools, even using referenda to do so. This must include significant numbers of voters who did (and still do) support Act 10. It’s numerically impossible that every winning referendum came about only with the votes of those opposed to Act 10; even obviously conservative districts have supported referenda.

2. Waiting for an outcry against spending, of the kind outcry that this school district had in the past, is probably waiting for a lion who’s not there, and won’t show up.

3. Some referenda will fail, and some will only pass on a second try (still possible under our laws, mere legislation obviously notwithstanding).

4. It’s impossible that because most referenda pass, any referendum has a greater than ninety percentage chance of success. These votes are not like drawing lots, where nine of ten are drawn, without knowledge of what the lots look like. On the contrary, the minimum requirements of a school referendum require a stated amount sought and the purposes for it.

(Janesville not long ago proposed a municipal referendum where the city sought an amount but described no purpose for it. It failed, of course. By the way, the recommendation to submit a referendum without a stated purpose is an example of some of the worst municipal lawyering I can recall.)

5. There must be – in these many referenda that succeed – a successful gauging of what the community will bear. It’s not (I’ll assume it cannot be) only by chance that referenda succeed.

6. Even in a favorable climate, requests will have to be defensible, as even a favorable climate has limits.

7. What is that defensible amount, and what are those defensible purposes? I’m not sure.

8. Is it easier or harder to advance a referendum in a unified school district (that is, one that is made up from several towns)? I think harder, overall, for reasons I’ll state in a future post.

So, a revised assumption: that a referendum’s more likely to pass that I thought at the time of our last referendum, but there are still critical elements that make the high success rate of February 2016’s referenda deceptively reassuring.

Next week: What Not to Do When Seeking a Referendum.

THE EDUCATION POST: Tuesdays @ 10 AM, here on FREE WHITEWATER.

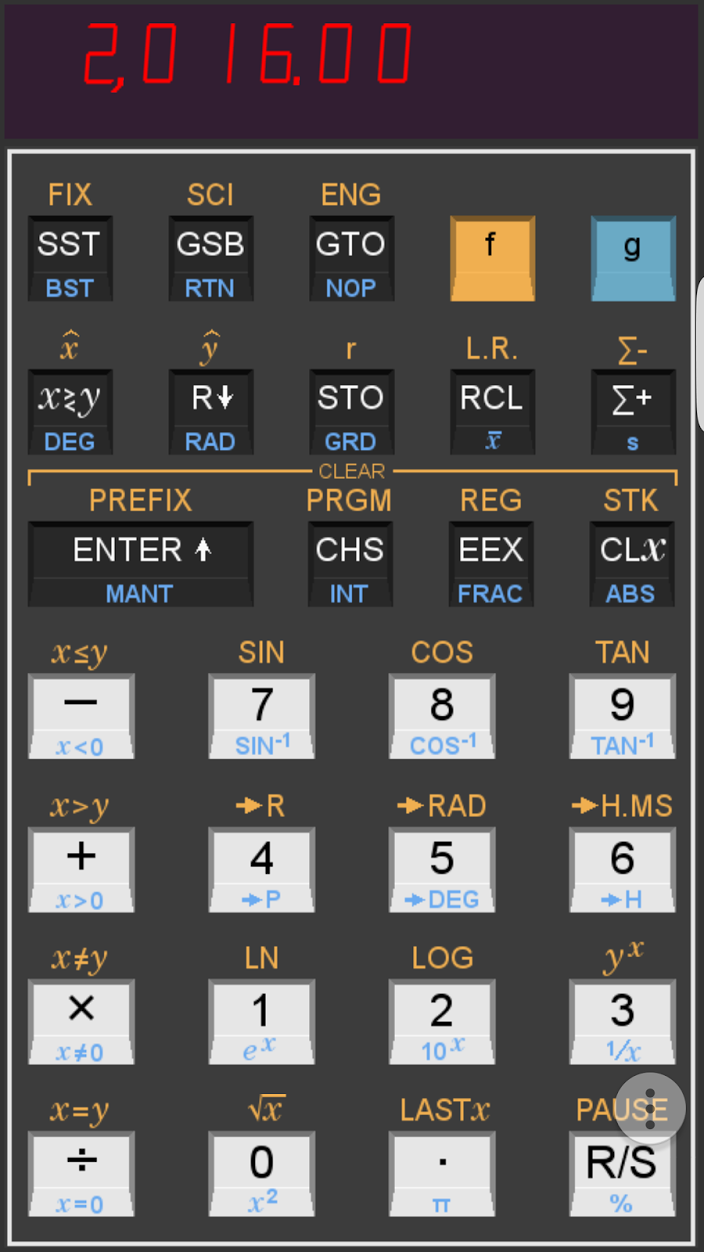

(About the picture for this series – it’s a screenshot of a calculator app for Android phones that emulates a Hewlett Packard 33C. I used an HP calculator in school, and they were amazing machines. My phone’s calculator app pays tribute to a fine machine of yore.)