Good morning, Whitewater

There is one public meeting scheduled today in the City of Whitewater: the Common Council meeting this evening at 6:30 p.m. in the municipal building. The agenda for that meeting is available online.

The National Weather Service predicts snow today, and a high of 17 degrees. The Farmers’ Almanac begins a new series, predicting conditions turning wet, “especially the Great Lakes.” I would have guessed as much.

Yesterday’s better prediction: NWS.

In our schools today, there is a Lincoln School Fifth Grade Choir Concert at 1:30 PM and 7 PM in the high school auditorium.

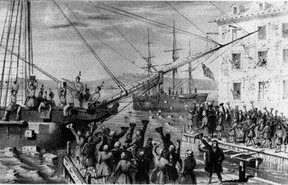

In American history for this day, in 1773, the Bostonians took action against British impositions and held the Boston Tea Party, as the History Channel recounts the event:

In Boston Harbor, a group of Massachusetts colonists disguised as Mohawk Indians board three British tea ships and dump 342 chests of tea into the harbor.

The midnight raid, popularly known as the “Boston Tea Party,” was in protest of the British Parliament’s Tea Act of 1773, a bill designed to save the faltering East India Company by greatly lowering its tea tax and granting it a virtual monopoly on the American tea trade. The low tax allowed the East India Company to undercut even tea smuggled into America by Dutch traders, and many colonists viewed the act as another example of taxation tyranny.

When three tea ships, the Dartmouth, the Eleanor, and the Beaver, arrived in Boston Harbor, the colonists demanded that the tea be returned to England. After Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson refused, Patriot leader Samuel Adams organized the “tea party” with about 60 members of the Sons of Liberty, his underground resistance group. The British tea dumped in Boston Harbor on the night of December 16 was valued at some $18,000.

Parliament, outraged by the blatant destruction of British property, enacted the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, in 1774. The Coercive Acts closed Boston to merchant shipping, established formal British military rule in Massachusetts, made British officials immune to criminal prosecution in America, and required colonists to quarter British troops. The colonists subsequently called the first Continental Congress to consider a united American resistance to the British.

The British response was typical, really — a siren’s call — to respond with ever greater control, restriction, and limitation. A small moment became a bigger one, through political arrogance.