Monday in Whitewater will be cloudy with a high of 38. Sunrise is 7:04 AM and sunset 4:22 PM for 9h 17m 32s of daytime. The moon is a waning crescent with 29.1% of its visible disk illuminated.

Whitewater’s Urban Forestry Commission meets at 4:30 PM.

On this day in 1972, Atari releases Pong, the first commercially successful video game.

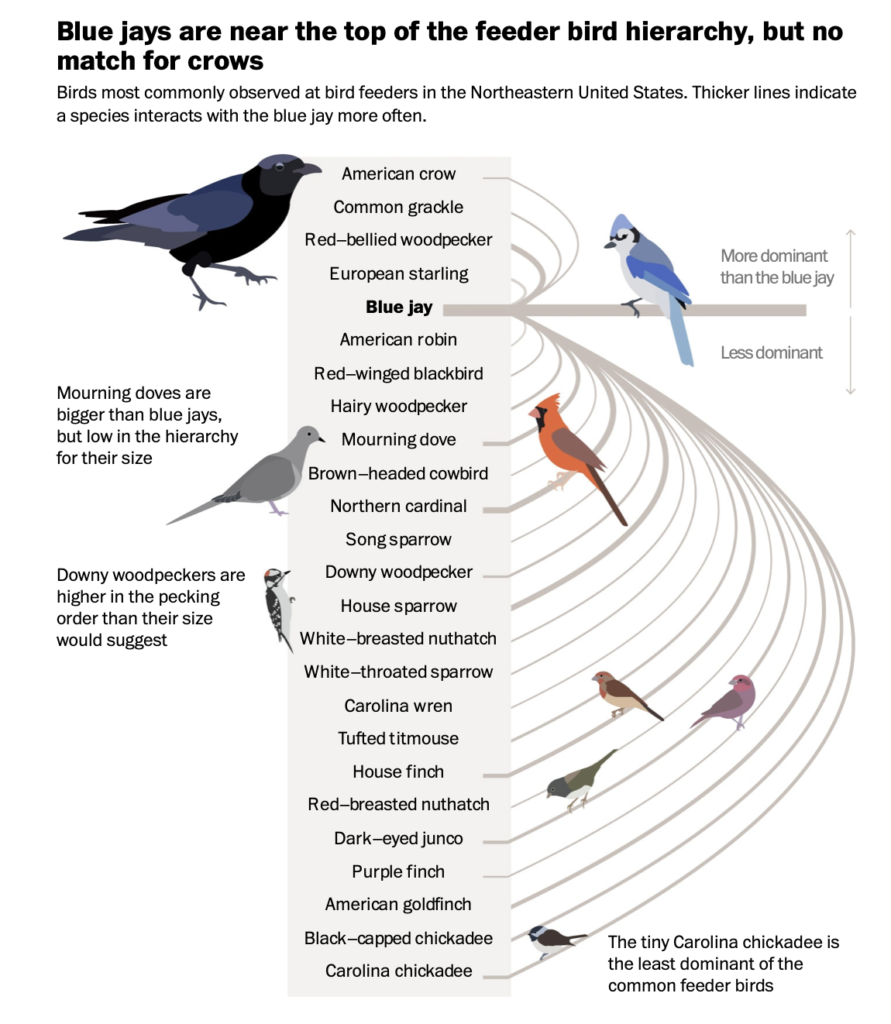

Andrew Van Dam and Alyssa Fowers report Which birds are the biggest jerks at the feeder? A massive data analysis reveals the answer (‘Presenting the ultimate bird-feeder pecking order’):

The interactions between birds in the park or at your backyard feeder may look like chaos, but they’re actually following the subtle rules of a hidden avian social order.

Armed with a database of almost 100,000 bird interactions, experts known as ornithologists have decoded that secret pecking order and created a continentwide power ranking of almost 200 species — from the formidable wild turkey at the top to the tiny, retiring brown creeper at the bottom.

Their work illuminates an elaborate hidden hierarchy: Northern mockingbirds and red-bellied woodpeckers are pugnacious for their size, but both would give way if a truly dominant bird like an American crow descended upon the feeder. Tiny hummingbirds can’t afford to lose precious seconds of feeding time and thus punch way above their weight, while the pileated woodpecker, whose fearsome bill and impressive build gives it the aspect of a holdover pterodactyl, actually proves docile for its size.

Among the most common feeder visitors, the American crow is king, while tiny chickadees get pushed around by just about everybody. The oblivious mourning dove outweighs many rivals but proves relatively peaceful. And lively goldfinches love to squabble but are limited by their half-ounce size.

Blue jays are near the top of the feeder bird hierarchy, but no match for crows

Birds most commonly observed at bird feeders in the Northeastern United States. Thicker lines indicate a species interacts with the blue jay more often.

“You see it at your feeder, and you’re like, ‘Oh, that woodpecker? He’s a mean one!’ and you ascribe these individual preferences to birds at your feeder,” said Cornell University ornithologist Eliot Miller. “But if you zoom out, all these same interactions are happening millions of times in cities across the continent, and the way they play out is predictable.”