Good morning,

Today’s forecast calls for a sunny day, with a high of fifty-seven degrees.

This afternoon, at 4 PM, there will be a groundbreaking ceremony for Whitewater’s multi-million dollar, taxpayer-funded Innovation Center. If you’re not able to attend, you can always catch the video of the groundbreaking for the Whitewater University Tech Park, held in September 2009:

http://www.blip.tv/file/2688983

If they’d wanted, those so inclined might simply have set up a large screen near the site of the future Innovation Center, and projected the prior ceremony’s video, without the need for any attendees.

Now, that would have been an innovation.

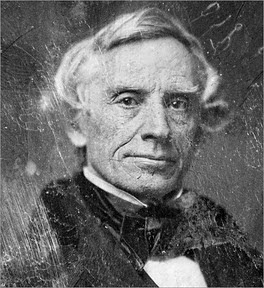

Wired recalls that on this day in 1791, Samuel F.B. Morse, ‘American Leonardo,’ [was] Born:

1791: Samuel Finley Breese Morse, inventor of the practical electromagnetic telegraph, is born in Charlestown, Massachusetts. He’ll also make waves in the art world and in politics.

Morse’s father, Jedidiah, was the co-inventor of cerographic sterotypy (a wax-based printing process), and he improved the bathometer (for measuring water depth). He also wrote and edited geography textbooks and with his brother founded the New York Observer.

S.F.B. Morse went to Yale College, were he studied under mathematician Jeremiah Day and chemist Benjamin Silliman. Neither noticed any particular spark in their young student….

He helped found the National Academy of Design in 1826 and served as its first president all the way through 1845. He also enjoyed considerable popularity as a lecturer on art.

Morse returned to Europe in 1829 to study the old masters, and he stayed in France and Italy until 1832. By the time he returned, he was regarded as one of America’s foremost painters.

Congress was deciding who should paint four of the great panels on the walls of the rotunda of the Capitol Building. Four of the eight panels had already been completed by John Trumbull, president of the American Academy of Fine Arts, from which Morse’s group had seceded.

Many people — Morse included — expected Morse to be among those chosen to paint the four remaining panels. Former President John Quincy Adams, who was then a representative from Massachusetts, submitted a resolution to allow foreign artists to do some of the work, suggesting that American painters had not yet achieved the caliber of greatness required for such monumental work.

Novelist James Fenimore Cooper, a friend of Morse, wrote an anonymous letter to the New York Post defending the native talent. In the midst of a running feud between Morse and Trumbull, the letter’s effect was the reverse of what Cooper intended.

The committee in charge of selecting the artists thought that Morse had written the letter, and they rejected him as a possible candidate. (The panels were eventually painted by John Vanderlyn, William Henry Powell, John Gadsby Chapman and Robert Walter Weir, with all of whom you are no doubt familiar.)

To console him, Morse’s friends got together and commissioned a work from him. He made a few sketches but decided his career as an artist was over. He returned the advances on the commission and never picked up a brush again.

The downturn in his artistic fortunes would be a boon to communications.

On the ship back from Europe in 1832, Morse had started to contemplate the concept of transmitting messages instantaneously by using electricity. And the more he thought about it, the more he became fascinated with it.

Taking a professorship in art at New York University to support himself, Morse worked four years to produce his first model of the telegraph. He also took time to run for mayor of New York City on the anti-immigrant, anti-Abolitionist ticket of the Nativist Party. He lost.

Morse applied for a patent on the telegraph in 1837 and gave the first public exhibition of his device to scientists the following year. He ran for mayor as the Nativist Party candidate again in 1841. He lost again.

Morse petitioned Congress for development funds to work out the practical problems of the telegraph and to build a proof-of-concept system. Congress gave him $30,000 (more than $800,000 in today’s money) in 1842 to build a test line from Baltimore to Washington, D.C.

The first official transmission on the completed 41-mile line came May 24, 1844, with the grandiose message: “What hath God wrought?” (What hath Sam writ?)….

A century after the invention of the telegraph, biographer Carleton Mabee called Morse the American Leonardo. But Morse had once written to Cooper, “I have no wish to be remembered as a painter, for I never was a painter.”

He got his wish.