Good morning,

Whitewater’s forecast calls for a chance of thunderstorms with a high of eighty degrees.

The City of Whitewater has a busy municipal calendar today. At 4 p.m., there were be a meeting of the Parks & Recreation Board. The meeting agenda is available online.

At 6 p.m., there will be a meeting of Whitewater’s Planning Commission. The agenda, with a packet of documents related to the meeting, is available online. It’s an improvement for Whitewater over past practice, and brings our city into alignment with the sound practice of putting documents online, in advance of the meeting, for residents to review and consider. I’ve written about this previously. (See, It’s In Your Packet and It’s Online for All: The City of Beloit’s Good Government Example.)

I’ll blog on tonight’s Planning Commission meeting, with topics at that meeting including a residential zoning overlay for the Starin Park neighborhood, and a proposed expansion of our Walmart.

At 6:30 p.m., there will be a meeting of Whitewater’s library board. The agenda for the meeting is available online.

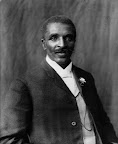

It’s the anniversary of George Washington Carver’s birthday — he was born in 1865, and died in 1943. Upon his death, the New York TImes published an obituary describing his life’s accomplishments, albeit a description that was informative yet deeply condescending:

Dr. George Washington Carver, noted Negro scientist, died early tonight in his home at Tuskegee Institute. His age was 78.

Dr. Carver had been in failing health for some months and was confined to his bed for the last ten days.

He became a member of the Tuskegee Institute faculty in 1894 and had been attached to the Negro institution ever since.

Dr. Carver was recognized as one of the outstanding scientists in the field of agricultural research. He discovered scores of uses for such lowly products as sweet potatoes, peanuts and clay. From the South’s red clay and sandy loam, he developed ink, pigments, cosmetics, paper, paint, and many other articles.

No Ambition for Riches

Dr. Carver, paying no attention to his clothes and refusing to make money on his discoveries, simply devoted his life to scientific agricultural research, to enable his colored brethren to make a better living from the soil in the South.

He became such an authority on cotton, the peanut and the sweet potato that he ended with a place among important white men. His name is in “Who’s Who in America,” and he was accorded a membership in the Royal Society of London.

“Who’s Who” lists him as an educator and follows immediately with the information, which he supplied, that he was “born of slave parents on a farm near Diamond Grove, Mo., about 1864; in infancy lost his father and was stolen and carried into Arkansas with mother, who was never heard of again; was bought from captors for a race horse valued at $300 and returned to former home in Missouri.”

Because he was a puny boy who got his growth late, he was allowed to run around as a household pet without being put to heavy work. Outdoors he learned about trees, shrubs and insects and liked to paint and draw them. In the kitchen he picked up much knowledge of cooking and of canning fruits and vegetables which later was to serve his people. In the parlor he learned something of music.

It’s also the anniversary of the Etch A Sketch. Wired offers a story entitled, Etch a Sketch? Let Us Draw You a Picture that describes the device:

The technology behind this children’s toy is both simple and complex. Simple, in that an internal stylus is used, manipulated by turning horizontal and vertical knobs to “etch a sketch” onto a glass window coated with aluminum powder.

Complex, because the Etch a Sketch employs a fairly sophisticated pulley system that operates the orthogonal rails that move the stylus around when the knobs are turned. The stylus etches a black line into the powder-coated window to create the drawing.

Along with the aluminum powder, the guts of the toy include a lot of tiny styrene beads that help the powder flow evenly when the sketch is being erased (by shaking), recoating the screen for the next drawing. As for how the aluminum powder sticks to the window, well, it pretty much sticks to everything.

Arthur Granjean, a Frenchman, was the Etch a Sketch’s inventor (he called it L’Ecran Magique, or “The Magic Screen”). After failing to get some of the bigger toy companies to bite, he sold his invention to the Ohio Art Company, which has manufactured it ever since.