Good morning,

Today’s forecast for Whitewater calls for a sunny day with a high temperature of eighty-one degrees.

Whitewater’s Independence weekend events continue, and a full description is available at ww4th.com. Here’s what’s scheduled:

Festival Schedule

Friday, July 2nd

5:00 PM

Festival Opens

– Midway by Christman Amusement Opens

– American Legion Beer Tent Opens

– Food Vendors Open

Live Music Stage

6:00PM – Midnight – The Blue Olives w/ The Pipe Circus

10:00 PM

Fireworks

12 Midnight Festival Closes

Saturday, July 3rd (Kid’s Day)

12 Noon

Festival Opens

– Midway by Christman Amusement Opens (Arm Bands 12PM-4PM)

– American Legion Beer Tent Opens

– Food Vendors Open

12:00 noon – 4:00PM – Children’s petting zoo – Sponsored by Dalee Water Conditioning

1:00 PM – Minneiska Ski Show on beautiful Cravath Lake

Live Music Stage

Noon – 1:00PM – Cross Point Church Band

2:00PM – 3:00PM – EKiss O Musical

3:30PM – 5:00PM – Beyond Youth

5:30PM – 8:30PM – Saddle Brook

National Music Act!

9:00 PM – Heidi Newfield of Trick Pony – www.heidinewfield.com

12 Midnight Festival Closes

Sunday, July 4th

8:00 AM – 3:00 PM

26th Annual Car Show

10:50 AM

Whippet City Mile

11:00 AM

Whitewater’s 4th of July Parade

12 Noon

Festival Opens

– Midway by Christman Amusement Opens

– American Legion Beer Tent Opens

– Food Vendors Open

1:00 PM

Minneiska Ski Show on beautiful Cravath Lake

Live Music Stage

2:30PM – 5:00PM – Steve Meisner

5:00PM – 6:00PM – Shelley Faith

6:30PM – 7:30PM – Hours Left

8:00PM – Midnight – The Britins (Beatles Tribute Band)

10:00 PM

Fireworks

12 Midnight Festival Closes

On this day in Wisconsin history, Abraham Lincoln visited Wisconsin during the Black Hawk War. The Wisconsin Historical Society recounts his visit:

1832 – Abraham Lincoln Passes through Janesville

On this date Private Abraham Lincoln passed through the Janesville area as part of a mounted company of Illinois militia during the Black Hawk War. [Source: History Just Ahead: A Guide to Wisconsin’s Historical Markers edited by Sarah Davis McBride, p. 117]

Not merely the Janesville area — a Lincoln marker, describing his trip, is just outside Whitewater’s city limits. Here’s a link to others, entitled, LIncoln in the Black Hawk War. From that website, here are Lincoln’s remarks on his service:

Lincoln was 23 years old when the Black Hawk War broke out in 1832. He “…joined a volunteer company, and to his own surprise, was elected captain of it. He says he has not since had any success in life which gave him so much satisfaction.” [Autobiography for Campaign, 1860] Lincoln said that he didn’t see “…any live, fighting Indians…but I had a good many bloody struggles with mosquitoes…and I was often very hungry.” “… I bent a musket pretty badly on one occasion…I bent the musket by accident.” [Speech in Congress, July 27, 1848]

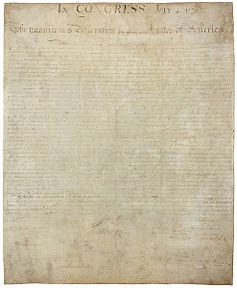

On this day in 1776, the Second Continental Congress voted for independence: “these United Colonies are, and of right, ought to be, Free and Independent States.”

Wired has a story about preserving the parchment paper on which the the Declaration, stating the justification for that July 2nd resolution, was written. In Preserving the Declaration, Tony Long writes that

During the Revolutionary War, the Declaration of Independence was rolled up and toted around like a Thomas Bros. map, although, given the vicissitudes of war, that’s perhaps understandable. Less understandable is what came later. Water was spilled on it while it was being copied in 1823. Then it was tacked up on the wall at the U.S. Patent Office for about 40 years, where it was subjected to a strong northern light.

Finally, the suggestion was made in 1903 that maybe it shouldn’t be exposed to sunlight and, oh, by the way, maybe it should be kept dry, too. The latter turned out to be a bad idea because the Declaration, which was written on parchment, actually needs a bit of moisture to keep from cracking

It wasn’t until 1951 that the first modern preservation efforts began. The document was sealed inside a bronze, bullet-proof glass case at the National Archives building in Washington, D.C. Humidified helium replaced oxygen to prevent further erosion, and the glass was filtered to cut down on light exposure.

Beginning in 1987, using camera equipment developed for the Hubble Space Telescope, preservationists were able to monitor the Declaration for even the most minute signs of fading or flaking ink.

The measures proved effective, so much so that the Declaration outlived its original protective case. After undergoing careful inspection for further erosion in 2003, the document was resealed in a titanium casement filled with inert argon gas. Similar preservation techniques are used to protect the Bill of Rights and Constitution.