If the process of waste digestion is merely a crude mimicking of animals’ digestion, and if the ingredients of waste digestion are discarded, partly-eaten food, animal carcasses, or animal & human excrement, and all of the chemicals and substances attached to any of them, then there remains an even more astounding truth: what comes out of a digester.

Just as with animals’ excretions of feces, urine, and of flatulence, waste digesters produce solids, liquids, and gases. The surprising truth is that the production of foul-smelling methane for sale entails dumping the digester’s resulting solids onto the ground, pouring its water into the environment, and often breaching its gases into the air by burning.

However odd and absurd it seems, the results of composting discarded and masticated food, the rotting carcasses of rendered animals, and animal & human excrement are returned to the environment. They are returned as solids, liquids, and gases, with added risk of the chemicals & diseases to which the digester’s original contents may have come into contact.

Sludge (‘BioWaste’ or “BioMass’).

A digester, like a stomach, does not digest food into neat canisters for ready transportation or storage. The composting process doesn’t produce tiny cans of cooking fuel. It produces, principally, a solid mixture of the dark and foul contents of the digester, itself: sludge. Truck after truck dumps load after load into the digester, and those contents do not stay there forever. Out they must come, in time, as cheeseburgers come out of people: as a mostly solid but wholly unpleasant substance.

To make room for more, these solids have to be dumped somewhere, somehow. They’re often spread on the ground. Although that seems like an ordinary process of fertilization, it’s hardly so: this is not, and will never be, the compost from one’s garden. Containment of disease causing agents, pathogens, is a constant concern of waste digestion.

So much so, that it’s a national focus of the USDA’s National Agricultural Biosecurity Center’s Consortium. See, Carcass Disposal: A Comprehensive Review. National Agricultural Biosecurity Center’s Consortium (August 2004).

From Chapter 7 on Anaerobic Digestion, Section 4.2, on Risk of Contamination:

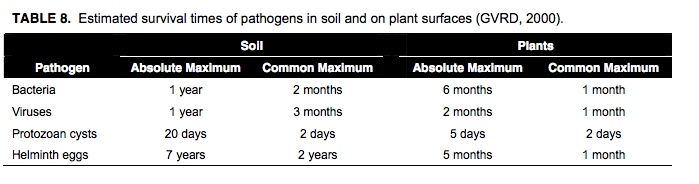

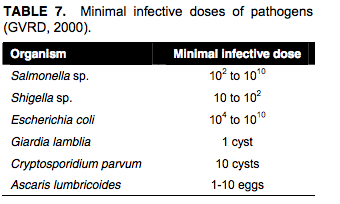

If the end products of anaerobic digestion (biosolids) are applied to land without pathogens being sufficiently reduced, the pathogens may pose a risk of contamination. Human beings and animals can be contaminated after being exposed to variable quantities of pathogens, as shown in Table 7. The infective dose depends on the type of pathogen and health of the host. Indeed children, older people, and people with compromised immune system are at greatest risk.

(Emphasis added.)

Generally, sludge accumulates in the bottom of the digester. Consequently, all pathogen agents capable of surviving in the digester could still be found in the end product several months after the introduction of pathogens in contaminated carcasses.

Careful research has established how long these pathogens might survive in the environment. Again, from the Consortium report, page 14:

Days, months, years.

One will not want to walk over those fields anytime soon.

Liquids: ‘Water, water every where, Nor any drop to drink’

Not merely solids, but liquids, too, will come from a digester. Proponents of these devices will look carefully for a way to dispose of the liquids from them. Perhaps they’ll seek to burden an existing municipal water facility with the additional, vast flow of water from the digester. They may likewise seek the entitlement to use an existing municipal permit from the state to allow final discharge into a nearby stream or creek.

This is especially troublesome in those areas (like much of Wisconsin) with karst areas, areas with bedrock that is easily dissolved by water, after which there are numerous cracks, sinkholes, and ways for water to seep down into the ground, and into people’s wells. Limestone is like this.

This is true for both liquids and solids in karst areas – they can contaminate the environment more easily than in areas with less porous bedrock.

Gases.

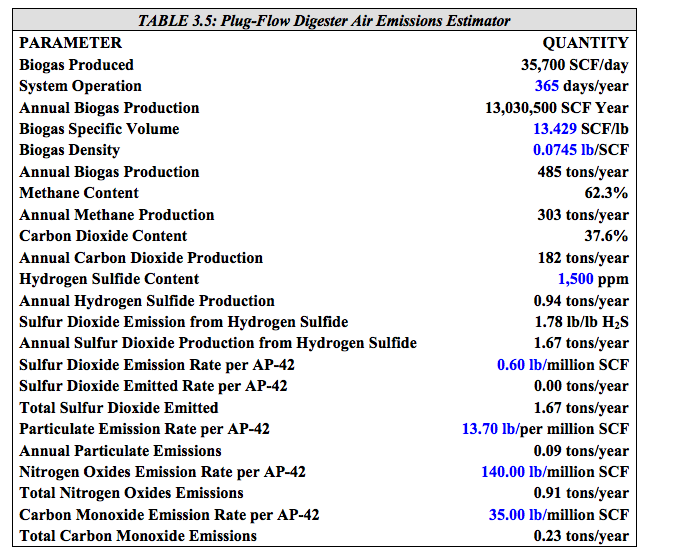

What, then, of the methane gases these digesters produce? They are produced, but not alone: other gases come from a digester, too. Even methane, while produced, isn’t always used – it’s sometimes burned off, when demand is low (as when competing natural gas is cheap) or when necessary despite demand.

Here, from Lusk, P. (1998). Methane Recovery from Animal Manures: A Current Opportunities Casebook. (3rd Edition. NREL/SR-25145. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Work performed by Resource Development Associates, Washington, DC., is a table from page 3-12 showing the gases a digester produces:

Methane, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide.

There you are – not in some faraway place, but in your own city or town.

Tomorrow: The Economics of Waste Digesters.